So who am I?

“Hi, what’s your name? What do you do? Where are you from?”

These are often the first questions we ask when we meet someone for the first time. I often get asked the latter question twice: “where are you from? Oh, I mean where are you from?”

What’s my name? My name is Kim Krings. What do I do? I serve as the Mission Trip Manager for a Catholic missionary organization. Where am I from? Humphrey, Nebraska, it’s a small town surrounded by corn fields. Oh, where am I from? I was adopted from China when I was a baby.

The response that usually follows is a lot of nodding. Maybe “Oh, I was going to guess Filipina or _____ (insert other Asian country),” or “Do you speak Chinese?” No, I don’t speak Chinese; I’ve lived 90% of my life in the Midwest. My family is basically all German.

I can usually tell right away if people are asking where I’m from or where I’m from. To tell you the truth, it’s a bit difficult to have people always guessing what I “am.” That’s the toughest—when people ask, “What are you?” What am I? A human, a sinner, a missionary, a beloved daughter of God.

Growing up, I had people tell me to “go back to China” or pretend to speak Chinese to me. People still do that today—make derogatory sounds pretending to speak Chinese, pull on their eyes to make them squinty, or make comments about me being good at karate or math. (Okay, I’m pretty good at math, though.) To varying degrees over the years, I’ve talked about these things with friends and family and am still learning how to share about my experiences growing up as an adopted Asian American.

I recently went to a conference that helped me go deeper into exploring and understanding my story. At the end of 2022, I went to Indianapolis for Urbana—a national missions conference primarily aimed at college-aged adults interested in learning how to live on mission. There were missionary groups from all over the world at this conference—hundreds of them!

Students could learn about how to serve any and everywhere in the world: Africa, China, Ukraine, the USA, the Middle East, etc. And serve in any and every capacity: sports/adventure camps, bible translations, education, etc. I was able to attend the conference with FMC as an exhibitor. We put up a table and took shifts inviting people to learn more about our mission and how to get involved. When not at the table, we could listen to talks or network with the other exhibitors.

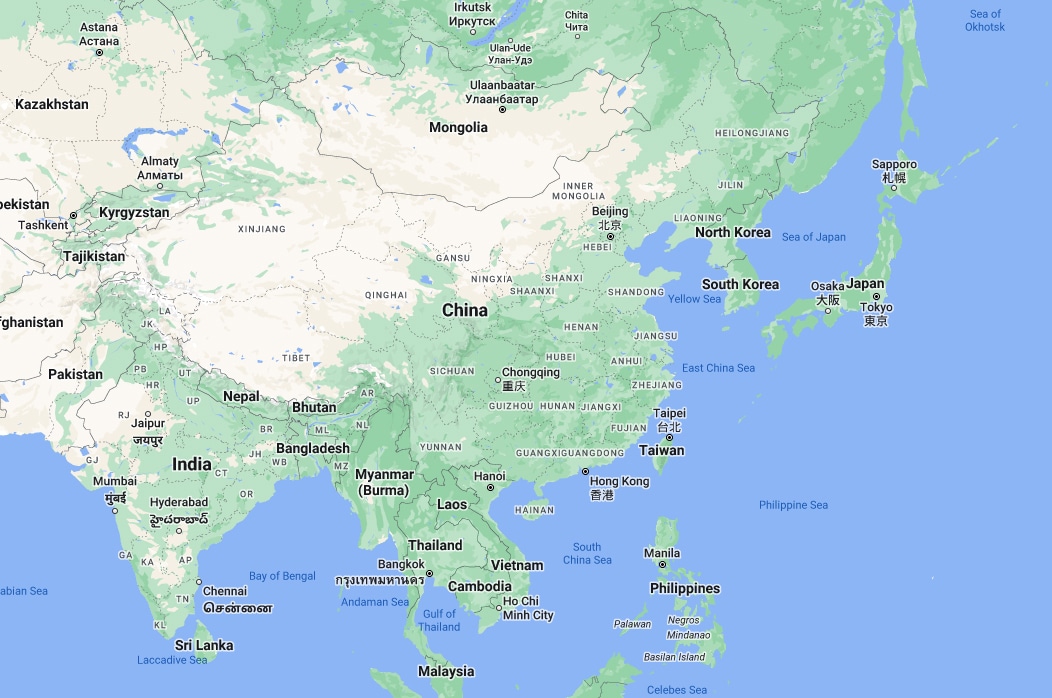

There is a group I met that has been doing missions in East Asia for over 150 years. (First off, wow!) It is illegal to evangelize in China so most of their names were not disclosed. I was moved by their speakers and their passion for this mission! Could I, as a Chinese American who doesn’t speak Chinese, make a difference in this mission? Would they reject me? Am I disqualified from this mission because I wasn’t raised in the culture of my birth country? What do I actually have to offer?

When I first joined FMC, I was originally sent to Taiwan to join a missionary who had been there the year prior. While my teammate and I spent less than two months there during the pandemic, I felt the difficulties of the mission. I was often asked to take pictures of locals with my very blonde, American teammate. People at restaurants or stores would talk directly to me even after she told them (in Mandarin) that she was actually the one who spoke Chinese. My Taiwanese friend’s mother turned away in disappointment (and disapproval?) when I told her I couldn’t speak Chinese.

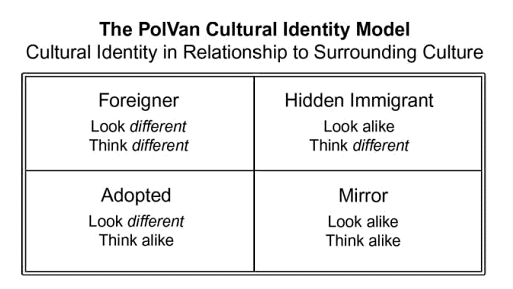

It’s very humbling (and difficult) for people to look at me thinking one thing, and then not have their expectations met. In the book Third Culture Kids by Polluck, Reken, and Polluck, the authors give names to what I had and have felt before. In America, I look different from most people around me, but I think alike, having grown up here. Thus, I am what they term “adopted.” In Taiwan (or if I should ever return to China to visit), I look alike but think differently. Thus, I am what they term a “hidden immigrant.” (see chart below.)

The representative from the Asia mission group listened to my story and held it with respect and honor. She offered me resources on how to get involved and asked me if I truly felt disqualified from the mission in East Asia. At times, I do. But I know it is the voice of the enemy discouraging me from ministering to the people and culture in which I was born. I often think of Esther in the Bible who was taken from her Jewish people and chosen by the king to be his wife. When Haman, a minister of the King, plotted to kill the Jews, Esther interceded on their behalf and saved her people.

In Hebrew, Esther’s name relates to the word “hidden.” I think about and pray with the beauty of her hiddenness and how the Lord used her as a vessel to minister to her people, though she didn’t live amongst them. In my own hiddenness or adopted-ness, I pray that I can embrace this, as Esther did, living into her calling as the beloved, with a soft heart for the culture she was born into.

So who am I, or what am I? I am a daughter of the King who called me into an adopted life, one of often hidden understanding. I am called by the Lord to pray and intercede for those who do not yet know the name and love of Jesus. I am a human, a sinner, a missionary, a beloved daughter of God.

Hello Kim! This is so well written 🙂

As a Chinese Singaporean, I have escaped most of those comments most of my life, although, growing up in a culture that is Asian but has strong Western influences, I do get you. Oh – studying in Australia I did have lots of the “Wow you speak really good English” kinds of comments. My English is actually way better than my Mandarin (which is embarrassingly barely existent).

Just wanted to say I’m so happy you undertook (or are thinking of undertaking) the mission in East Asia – the first time I went to China, I felt this huge need, for Christ, for them. I took a Chinese friend who was studying in Australia to a Christmas mass, where she saw someone praying and remarked, “she looks so beautiful, praying.” What she meant was that she had never seen anyone pray, and it struck her as something out of the ordinary. Maybe it was her first contact with something transcendent. There is much work to be done. And like you, I feel there is so much history and culture, that is my own and not my own (I felt the same in Taiwan – this culture is mine and not mine. Chinese culture is at the base of who I am, but definitely not all of it, perhaps not even the half).

Saying a small little prayer for you to go where He leads, which will always be the best 🙂 (the Chinese diaspora is practically all over the globe, so even if you ended up in say Spain or Brazil, you’d likely still be able to find a Chinese community to serve in if that’s where you’re called!) God bless 😀

Ps. I’d have loved to have grown up surrounded by corn fields