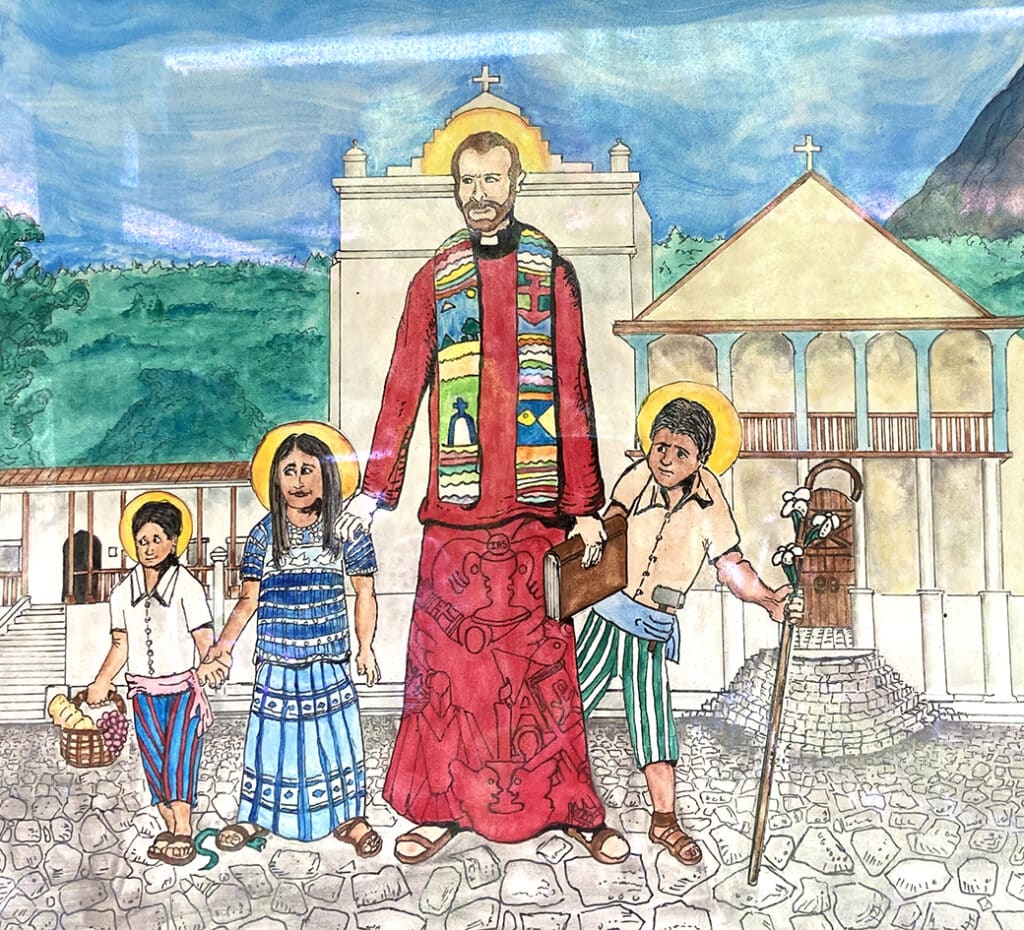

Fr. Stanley Rother, Missionary and Martyr

Only after four years of working with the Guatemalan children on Lake Atitlan did we realize we were part of the diocese where Fr. Stanley Rother served as a missionary and was martyred.

Fr. Stanley was born in Oklahoma and was ordained a priest of Oklahoma City in 1963. Five years after his ordination, he began working with the diocesan mission team in Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala, in the Diocese of Solola-Chimaltenango.

Before Fr. Stanley and the other missionaries arrived in Santiago Atitlan in 1968, the Church there had not benefited from the presence of a priest for about 100 years. What practice of faith remained was a mixture of Catholicism and Mayan worship.

The missionary team of American priests, sisters, and lay people served for several years together in the wake of Vatican II and the cultural changes taking place in the U.S. There were often disagreements among the missionaries about how to live an authentic Catholic life. Several missionaries participated in heated discussions in the evenings after dinner. Fr. Stanley either retreated to his room or went to visit the people. His magnanimous character enabled him to rise above the disagreements and focus on his role as a shepherd.

After time, Fr. Stanley was the only person from the diocesan missionary team remaining. He served the indigenous Tz’utujil people during their civil war, a time of great suffering and danger. Having grown up in a solid German family on a farm in Oklahoma, he had much to offer the people. He knew how to work a farm and read the weather, and he offered his construction and mechanical skills to the people. Fr. Stanley’s gifts were more practical than intellectual, as he always struggled in school. In fact, most people are in awe that he became fluent in the Tz’utujil dialect given his challenges with Latin.

Fr. Stanley loved the people and cared for them the way a shepherd cares for his lambs. He visited them, ate whatever they set before him, built them a hospital and a school, played with the children, and labored side-by-side with farmers. He approached the Tz’utujil people in a gentle, humble way. He said Mass in the city on Sundays, then traveled to the farms to say another Mass. He had a team made up of local religious sisters, catechists, and seasonal missionaries serving the people with him.

In the late 1970s, civil unrest increased due to political tensions. Some of the catechists started disappearing. Farms were burned, destroying families’ livelihood. At one point, soldiers occupied the town, threatening the peaceful citizens. Fr. Stanley spoke up and challenged the soldiers, asking why under their “protection” the people were disappearing. The missing and dead men left behind widows and children whom Fr. Stanley cared for as best he could. He hid some of his catechists and arranged safety for his pastoral associate. He felt a responsibility to protect his flock.

Rumors circulated that Fr. Stanley was on the soldiers’ hit list. He was called back to the U.S. by his bishop for his own safety. While home, Fr. Stanley met with childhood friends and spoke before congregations, sharing the horrific violence and suffering of the Guatemalans, particularly the indigenous people. His stories were received with mixed responses. Though most people were sympathetic, some questioned Fr. Stanley’s political views. A view on the politics of the time was inevitable due to the fact that they were living in war. Although Fr. Stanley never sought to be involved in politics—in fact, he intentionally avoided them—he did live in a situation of political turmoil. So despite his best efforts, his talks explaining the suffering of the people were construed as political by some.

Fr. Stanley spent several weeks in the safety of his family home in Oklahoma. Eventually, he chose to return to his flock with permission from his bishop, saying, “A shepherd cannot run at the first sign of danger.”

He flew back to Guatemala, his safety threatened perhaps more than he realized. Incredulously, a man from a parish in Oklahoma reached out to the Guatemalan embassy and accused Fr. Stanley of being a traitor who was helping bring down the current political regime. Fr. Stanley’s life was already threatened, but that seems to have been the tipping point.

Knowing his life was in danger, Fr. Stanley slept with his shoes on. He wrote to his bishop and friends about his fears, yet he chose to stay. He was determined to fight back, should anyone attack him. On July 28, 1981, masked men broke into the rectory at night and attacked. There was a struggle that ended with Fr. Stanley’s death. He was immediately regarded as a martyr and saint by the local people.

Today, visitors to Santiago Atitlan can go to the church where Fr. Stanley served. It may be hard to find a seat, as it is often packed with people. The adjoining courtyard is generally filled with parishioners cooking, eating, and talking together. It is common to see people visiting the Blessed Sacrament in the perpetual Adoration chapel.

In the room where Fr. Stanley was killed, his blood is still on the floor, and his personal belongings are on display. One of the items preserved is a copy of the New Testament in Tz’utujil, a translation project which he commissioned. In the church, his heart is buried at a side altar dedicated to his memory, and a vial of his blood is in the main altar. The rest of his body was transported back to Oklahoma.

Fr. Stanley is a martyr of our time. He lived a simple life as a missionary, serving among some of the poorest people in Guatemala for many years. By giving his life, he inspired the faith of the Guatemalan people, resulting in many religious vocations. His witness has inspired the people in his home diocese, where a shrine has been built in his honor, as well as missionaries and Catholics around the world.

Fr. Stanley Rother was beatified in 2017. This shepherd who gave himself for his lambs in imitation of the Good Shepherd brings hope to our world.

Blessed Stanley Rother, pray for us!

Comments are closed